One interesting result that I always enjoy teaching in my game theory class is Feddersen and Pesendorfer's "Convicting the Innocent: The Inferiority of Unanimous Jury Verdicts under Strategic Voting." Their result suggests that if jurors vote strategically, then requiring unanimity to convict may actually lead to more incorrect convictions. While this result is fairly unintuitive at first, it can be very clear once the students understand strategic voting. One of the biggest difficulties is convincing the students that people may actually vote strategically in jury trial.

To help highlight this point in my class, I told the students that they had a pop quiz, which would consist of one multiple choice math question with two possible answers. If the class answered the question correctly, I promised them that I would bring them a snack to enjoy during the last day of class. The question was:

From Lafayette, IN to Chicago, IL is 126 miles. Car A heads North (Lafayette to Chicago) at 30 miles per hour and has a cheetah with very good endurance in the passenger seat. Car B heads South (Chicago to Lafayette) at 20 miles per hour. The cars leave their respective locations at 7:00AM EST in the morning. When car A leaves, the cheetah jumps out of the car and starts running 70mph toward car B. When it reaches car B, it turns around and goes back toward car A. It continues to run back and forth between the two cars until they meet. How far does the cheetah run before the two cars meet? HINT: The cheetah reaches car B for the first time at exactly 8:24AM.

Option A: The cheetah runs exactly 176.4 miles

Option B: The cheetah runs a different amount than 176.4 miles.

I gave the students 2 minutes to answer the question. The catch is that the students have to take this pop quiz as a class and vote on the answer. The voting is done with a unanimous voting rule. If everyone votes for option B, that is the class' choice. If even one person votes for option A, then that is the class' choice. I warned them that a student should only vote for option A if they were very confident in their answer, otherwise they might ruin the chance for the rest of the class to earn a reward on the last day of class. Option A is, in fact, correct. (Those interested in the math should check out the Appendix, which includes a nifty John von Neumann anecdote.) Voting was done with a MobLab survey. After voting, I asked them the following follow-up question:

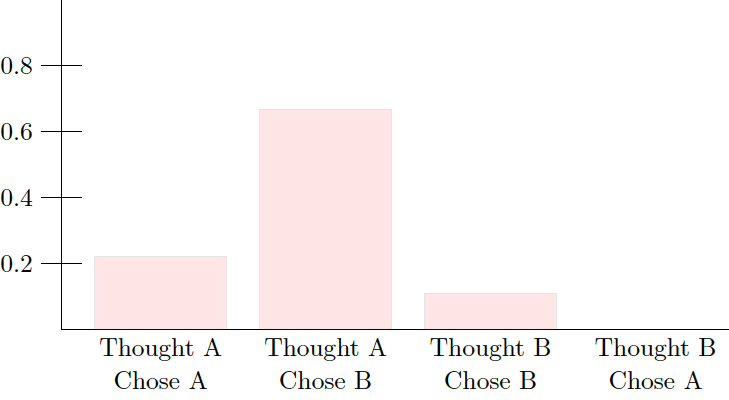

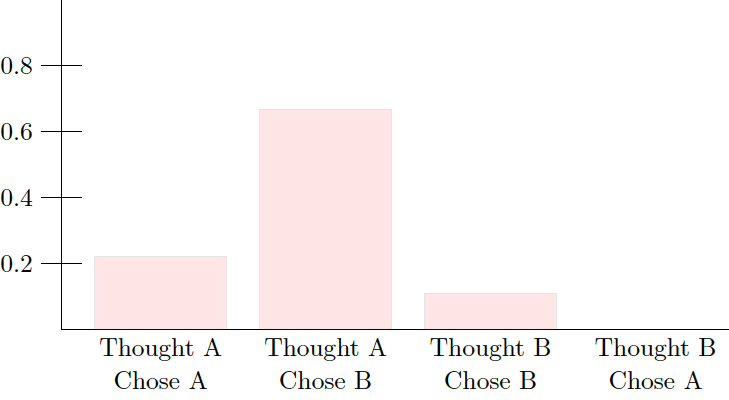

I thought option A was correct and chose option A. I thought option A was correct but chose option B. I thought option B was correct and chose option B. I thought option B was correct but chose option A. Their responses:

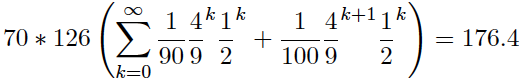

The responses show that almost 90% thought that option A was correct, but nearly 75% of the students that thought option A was correct still chose option B because of the voting rule. Also notice that only about 10% of the students thought that B was the correct answer, and all of them voted for B. We can draw comparisons to a jury voting situation where option A is acquit, and option B is convict. Even though most students thought option A was correct (innocent defendant) a large proportion of them still decided to vote for option B (to convict). In this case, voting for option B allows you to defer to other students that may be better at math. Similarly, in a jury trial, voting to convict allows a juror to essential defer their decision to other jurors who may be more confident about the verdict. This example hopefully highlights why someone may want to vote strategically in a situation like this.You can solve it directly by formulating this as an infinite sum, Alternatively, you can see that the cars are traveling toward each other at 20+30 miles an hour which will take 126/50 = 2.52 hours for them to meet. Since the cheetah is running for 70 miles per hour until the cars meet, it will run a total of 2.52*70=176.4 miles.

Want to see what other kinds of voting experiments you can run with your students? Get in touch with our team! We are eager to set up our economics games for your class!

To help highlight this point in my class, I told the students that they had a pop quiz, which would consist of one multiple choice math question with two possible answers. If the class answered the question correctly, I promised them that I would bring them a snack to enjoy during the last day of class. The question was:

From Lafayette, IN to Chicago, IL is 126 miles. Car A heads North (Lafayette to Chicago) at 30 miles per hour and has a cheetah with very good endurance in the passenger seat. Car B heads South (Chicago to Lafayette) at 20 miles per hour. The cars leave their respective locations at 7:00AM EST in the morning. When car A leaves, the cheetah jumps out of the car and starts running 70mph toward car B. When it reaches car B, it turns around and goes back toward car A. It continues to run back and forth between the two cars until they meet. How far does the cheetah run before the two cars meet? HINT: The cheetah reaches car B for the first time at exactly 8:24AM.

Option A: The cheetah runs exactly 176.4 miles

Option B: The cheetah runs a different amount than 176.4 miles.

I gave the students 2 minutes to answer the question. The catch is that the students have to take this pop quiz as a class and vote on the answer. The voting is done with a unanimous voting rule. If everyone votes for option B, that is the class' choice. If even one person votes for option A, then that is the class' choice. I warned them that a student should only vote for option A if they were very confident in their answer, otherwise they might ruin the chance for the rest of the class to earn a reward on the last day of class. Option A is, in fact, correct. (Those interested in the math should check out the Appendix, which includes a nifty John von Neumann anecdote.) Voting was done with a MobLab survey. After voting, I asked them the following follow-up question:

The responses show that almost 90% thought that option A was correct, but nearly 75% of the students that thought option A was correct still chose option B because of the voting rule. Also notice that only about 10% of the students thought that B was the correct answer, and all of them voted for B. We can draw comparisons to a jury voting situation where option A is acquit, and option B is convict. Even though most students thought option A was correct (innocent defendant) a large proportion of them still decided to vote for option B (to convict). In this case, voting for option B allows you to defer to other students that may be better at math. Similarly, in a jury trial, voting to convict allows a juror to essential defer their decision to other jurors who may be more confident about the verdict. This example hopefully highlights why someone may want to vote strategically in a situation like this.

Mathematical Appendix

There are two ways that the question can be answeredReferences

Fedderson, Timothy and Wolfgang Pesendorfer, "Convicting the Innocent: The Inferiority of Unanimous Jury Verdicts under Strategic Voting," The American Political Science Review, 1998, 92 (1), 23-25Want to see what other kinds of voting experiments you can run with your students? Get in touch with our team! We are eager to set up our economics games for your class!